+++ATD, or Engineers, in SPACE!

Thursday July 16, 2015

Like a boss, right as the DSN showed a downlink from New Horizons, I tweeted,

Signal from New Horizons reads, "+++ATD" #plutoflyby

— James P. Howard, II (@howardjp) July 15, 2015In 2001, I worked for a company called Wavix and we were building ground terminals for uplink/downlink communications with a small satellite constellation we operated.1 It connected to a local PC to provide email services over the spacelink. This, it turns out, was the coolest job I ever had.

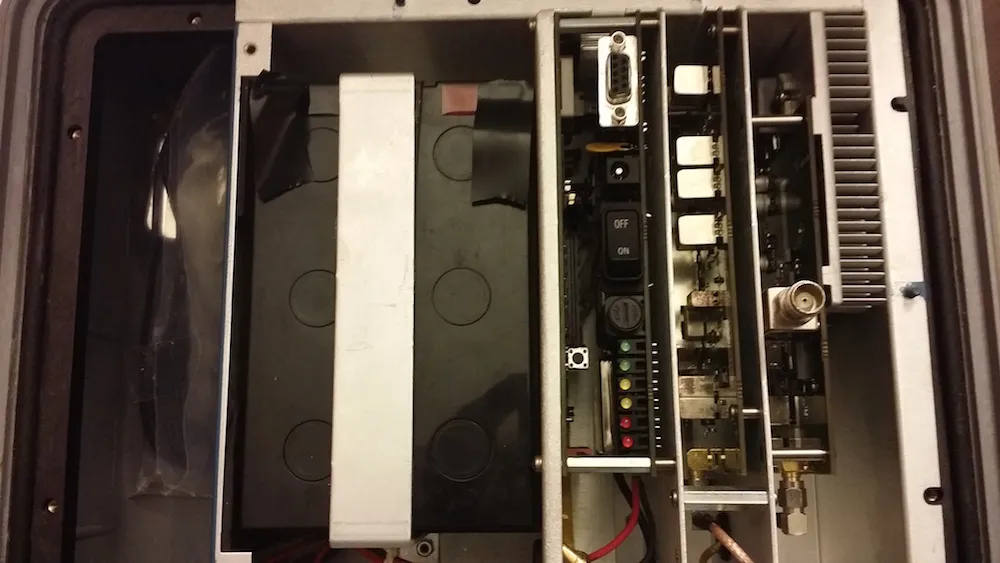

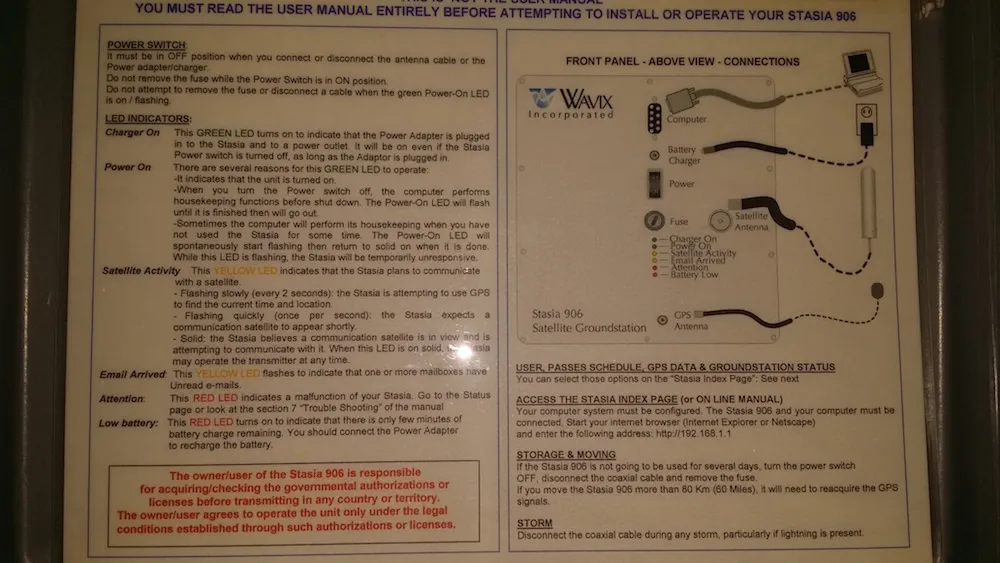

The terminal, the Stasia 906, was a StrongARM SBC running Linux. There was a GPS receiver and an RF transmitter and receiver, all jammed inside a Pelican case.

The hack I was proudest of was a surreal patch to the Linux kernel. The terminal had an RS-232 on the front and the user would connect a serial cable from the PC to connect. The idea was that the terminal would provide IP services over the wire and run mini POP and SMTP servers for mail transfer. But we couldn’t figure out how to get the link up after booting.

We could hotwire the PPP driver straight to the serial line, but Windows (we presumed was the client was running Windows) couldn’t just start PPP. It wanted to call you first. So one day, I tore open the Linux kernel code and added a minimally compliant Hayes modem command set to the serial driver code. It didn’t do anything but pretend to be a modem. It would happily dial whatever number you put in. And by that, I mean it threw away the numbers, pretended to connect, then launched the PPP daemon. It could also accept hangups, too, which was great, since we could then gracefully end the connection.

The Hayes modem command set was an abomination since it was inline. The “+++” above’s sole purpose is to capture the attention of the modem and say, essentially, “Stop what you’re doing and maybe do something else.” During this time, data could not be sent or received. The “ATD” command I gave put the modem into communications mode, by telling it to start the data connection. It assumed the phone was dialed and the receiver had picked up, it would start with the crazy squealing, for those of you old enough to remember such things.

Another awesome thing I did there was write a driver for the GPS unit. This was back in 2001, so there weren’t GPS units everywhere. The ones we had were terribly unreliable and couldn’t get a signal on a cloudy day. Also, they didn’t know about leap seconds, so they were all about 12 seconds too fast. But I wrote the code to synchronize the time on the terminal to it (accounting for leap seconds, since they didn’t). Also, I set the location so the terminal would know where it was, too, and could plan for an overhead satellite pass.

Passes were infrequent. Usually only four a day (two satellites, two passes each), but we were happy to have two usable passes per day. During this time, we did uplink and downlink. Mail was sent and received over AX.25 at 9600 bps. Our own uplink and downlink happened in Landover, Maryland. We operated at 56k bps, but still used AX.25. The last really neat thing I did there was how we managed the mail flow from Internet through to the satellite. We didn’t write a line of code. We turned on UUCP and gave each ground terminal both an Internet address and a bang path. We took in mail over SMTP and ran it through the UUCP gateway, which just queued it for upload on the next pass. Had I been cleverer, I would have called it an enterprise service bus.

I was originally hired by Dr. Jeff Shaumeyer and John Borden, who had previously worked together at the University of Maryland on Project Zeno. I was hired to be a systems administrator, and that was my job title. But, really, it only took a couple of weeks to standardize PC deployments and recable the place. And I knew C, so I started taking on development work. I did a bunch of other neat things that are harder to explain, like abusing Linux semaphores and writing a custom encrypted backup system from scratch.

These were just things that needed to get done. That’s the best part of working for a small business. On the day I started, the company doubled in size from four to eight people.

I was there for just about ten months before we ran out of money and everyone was laid off. And that ended my career as an embedded systems engineer.

The pictures are my old development system. The hardware should be fully functional. Believe it or not, I acquired it on Ebay years after we went defunct. The same one from my desk.

The only word in this sentence not an exaggeration is “small.” ↩