Lessons on Invisible Authority and Expert Power from Alien Observers

Tuesday November 12, 2024

Imagine this: an alien captain named Kleck is stationed on a human space fleet base, tasked with understanding human military ranks. He’s pretty confident he’s got it figured out–after all, his species uses a beautifully straightforward color-coded rank system. Purple is for generals, blue is for captains, green for lieutenants, and so on. To Captain Kleck, this system is as logical as it gets. But then he sees something that makes his antennae twitch. A human doctor with no visible insignia or rank walks onto the scene and starts ordering around high-ranking officers. And they listen.

This science fiction story about Kleck and “Doc” (Dr. Chen) offers a surprisingly relatable look at real-world power structures. It’s funny and a little surreal, but it raises important questions: What is authority based on? When does expertise outrank formal hierarchy? And how do power dynamics shift in fast-paced, unpredictable situations?

In breaking down this story, we will explore a few central ideas from organizational theory: formal vs. informal power, the concept of situational authority, and how rank on paper doesn’t always translate to actual control. We’ll also look at how expertise–especially in life-and-death situations–can override traditional hierarchy, even if it’s invisible in the organizational chart. Buckle up, because it turns out that Captain Kleck’s bewilderment with human authority structures has a lot to teach us.

Power structures are as neat as a box of crayons for Captain Kleck and his alien crew. In the Zexian military, rank isn’t something you must guess; it’s color-coded. Generals wear purple, captains wear blue, lieutenants get green, and the hierarchy goes down in a spectrum. Each color not only tells you who’s in charge but spells out what privileges they have–no one questions it, and nothing’s left to chance.

So, imagine Kleck’s shock when he sees a human doctor–a “Doc”–stride up to a decorated captain and demand the entire crew’s attention. She’s not wearing any colors or insignia that Kleck can recognize, and she’s clearly not a part of the military chain of command. But the captain listens. In fact, he immediately changes course and redirects his crew, all because this “Doc” told him to.

For the Zexians, this is baffling. They live by a formal power structure: clear, predictable, and universally recognized. In their world, you don’t give orders if you aren’t in the chain of command. But humans operate in a far more flexible way, where authority can shift based on expertise or even the demands of the situation. Dr. Chen doesn’t have military rank, but her knowledge and role as a medical expert give her a different kind of authority–the authority that comes from knowing what to do in a crisis.

Here, we see two kinds of power at work: formal power, which is based on a person’s position in the hierarchy, and informal power, which comes from knowledge, skill, or even personality. Formal structures are easier to spot–like the Zexians’ color-coded ranks–while informal structures are often invisible but just as real. In a medical emergency, Dr. Chen’s informal authority takes precedence over formal ranks because her expertise is what the situation demands.

In human organizations, especially dynamic ones, these two types of power can overlap, clash, or complement each other, depending on the need. For Kleck, though, the idea that someone without a formal title could outrank a decorated officer is as foreign as a purple general would be to us. But as we’ll see, this blending of formal and informal authority is what makes complex organizations both adaptable and resilient.

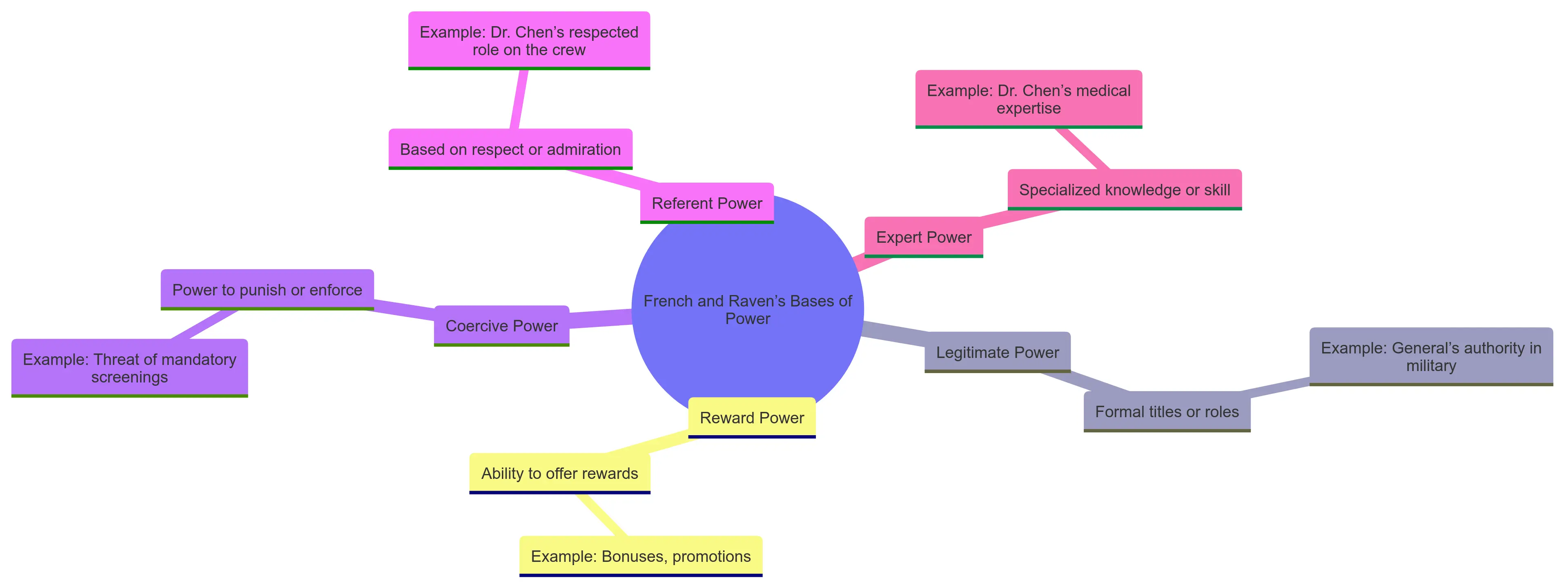

Understanding power dynamics isn’t just about knowing who’s “in charge.” Social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven described five main “bases” of power that shape authority in any setting: legitimate, reward, coercive, referent, and expert power. Each type plays a role in dynamic organizations, and Dr. Chen’s unexpected command over high-ranking military officers in the story is a perfect case study.

This is the most familiar kind of power–it’s what we recognize in formal titles and ranks. In the story, legitimate power is what Kleck expects to see in action: generals and admirals hold authority because their ranks are embedded in the structure of the military. To the Zexians, legitimate power is non-negotiable, clearly defined, and universally respected. When they see a high-ranking officer, they defer without question.

But as the story shows, legitimate power is only one form of authority, and it’s not always the highest. For Dr. Chen, her lack of military rank doesn’t limit her ability to command when expertise is critical, revealing the limits of legitimate power alone.

Reward power stems from the ability to provide benefits or rewards, encouraging others to follow directives. Although it’s not as overt in Dr. Chen’s role, her ability to ensure others’ health outcomes creates a subtle form of reward power. For instance, officers who listen to her can avoid medical issues and keep functioning optimally, which is a kind of reward in a high-stakes environment.

In dynamic organizations, reward power often comes from leaders who recognize and provide the resources people need to succeed–whether it’s extra support, mentorship, or even access to critical tools.

Coercive power, the “stick” to reward power’s “carrot,” is authority based on the ability to administer consequences or punishments. Though Dr. Chen doesn’t wield punishment in a traditional sense, her control over medical resources gives her a subtle coercive power. When a captain hesitates to redirect power from weapons to life support, Dr. Chen warns that failing to follow her orders could lead to “optional screening procedures” in his next physical–an amusing but effective use of coercive power.

Coercive power is common in traditional hierarchies, but when used sparingly and thoughtfully, it can also reinforce the importance of compliance in critical scenarios. In Dr. Chen’s case, her coercive power is less about punishment and more about emphasizing the need to prioritize health and safety.

Referent power is about personal influence–it’s the respect and admiration a person commands based on who they are, not just their rank or role. Dr. Chen’s demeanor and confidence lend her a natural authority that compels others to follow her lead, even when it disrupts formal hierarchy. Her reputation as a decisive, knowledgeable figure gives her referent power, which Kleck notices when people instinctively defer to her.

Referent power is critical in complex organizations because it inspires loyalty and trust, creating a cooperative environment where people want to follow strong leaders.

Finally, expert power is authority grounded in knowledge and specialized skills. This is the cornerstone of Dr. Chen’s influence in the story. When there’s a medical crisis, her expertise in health and safety protocols supersedes any military rank, and even the highest-ranking officers defer to her. Her knowledge is what everyone relies on to navigate high-stakes medical decisions, showcasing how expertise can outrank formal titles in life-or-death situations.

Organizations today are increasingly complex, blending formal structures with the need for flexibility and situational authority. Leaders often rely on multiple bases of power to navigate changing circumstances effectively. Dr. Chen’s role in the story illustrates this blend–while she doesn’t have legitimate power in the military hierarchy, her expert, referent, reward, and even coercive power allow her to exercise authority when it matters most. This multi-layered approach to power shows how authority in dynamic environments can shift depending on knowledge, relationships, and the immediate needs of the situation.

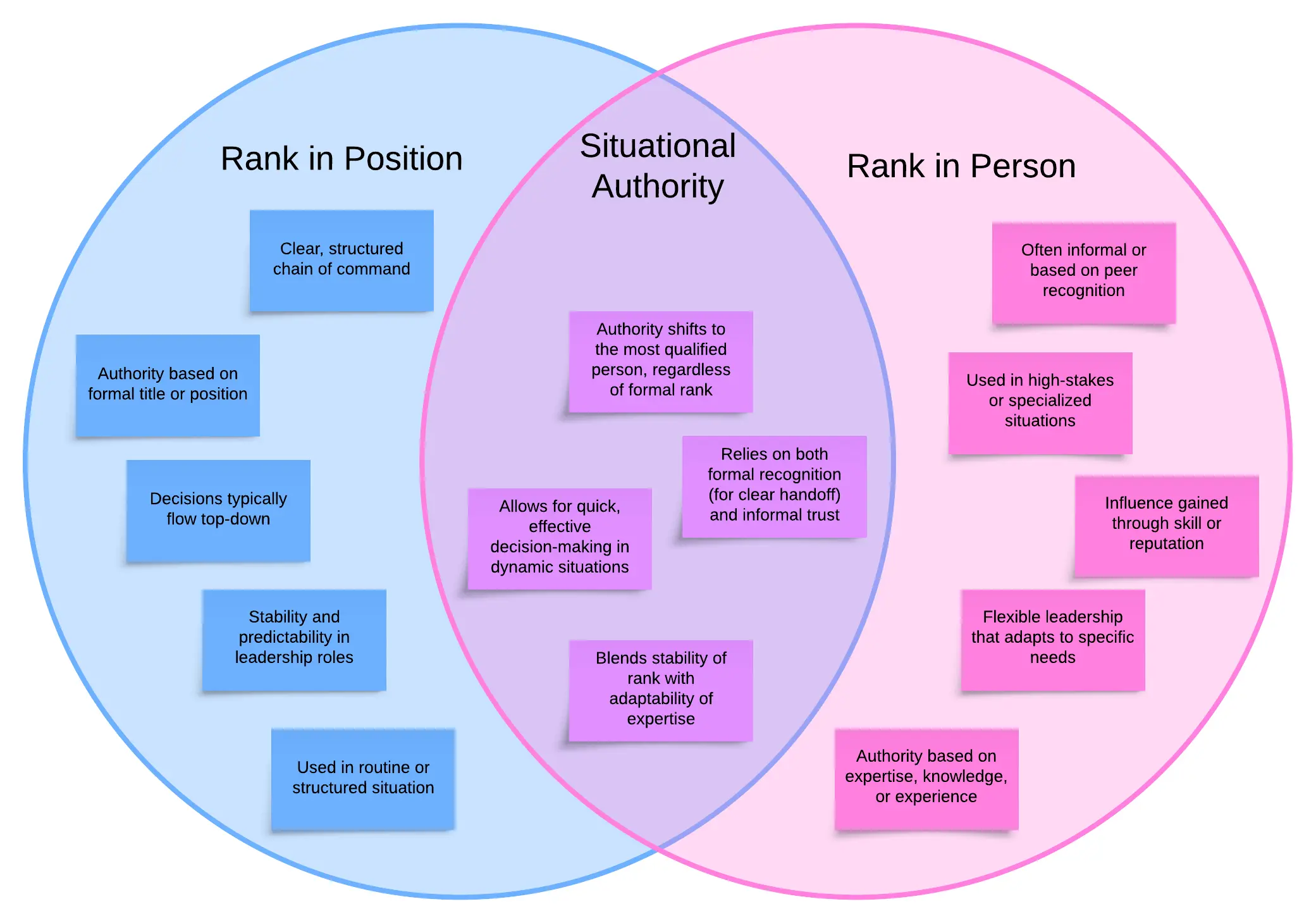

In most formal organizations, authority tends to come with a title. This is “rank in position,” where power is based on someone’s official role within a hierarchy. To the Zexians, Captain Kleck’s species, this is the only way authority works: a general outranks a captain, a captain outranks a lieutenant, and the color of your uniform says it all. In their world, titles mean everything, and they’re not just symbols–they dictate who gives orders and who follows.

But then there’s Dr. Chen, who throws Kleck’s understanding into disarray. She holds no military title, and technically, she isn’t in the chain of command at all. Instead, her authority comes from her medical expertise, which gives her “rank in person”–power that doesn’t rely on a formal title but on a person’s knowledge or experience. When a health crisis hits, it doesn’t matter that she’s not a military officer; Dr. Chen becomes the de facto leader because her skills are exactly what the situation demands.

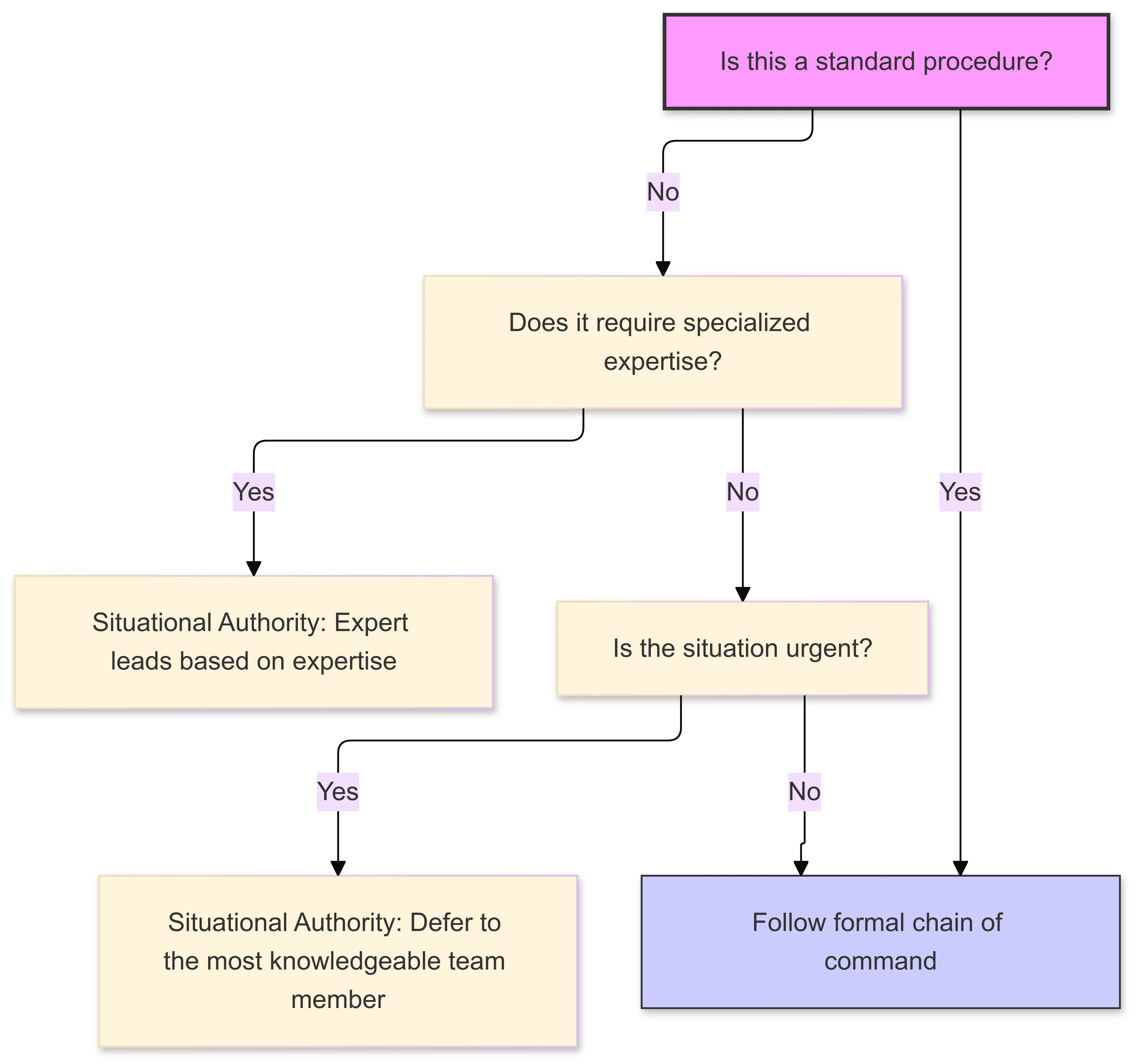

This clash between “rank in position” and “rank in person” is a key tension in many organizations, especially dynamic ones. Rank in position works well in predictable situations, where tasks follow a clear structure and each role has set responsibilities. But in high-stakes or specialized scenarios, like a medical emergency, the strict hierarchy of “rank in position” can slow down response times and leave critical decisions in the hands of those who may not have the right expertise. This is where situational authority comes in–authority that shifts based on who is most qualified for the task at hand.

For Kleck, the idea of situational authority is hard to grasp. In his mind, someone with no title should have no authority. But for humans, this flexibility can mean the difference between success and failure. When Dr. Chen steps in to give orders, she does so not because she outranks the officers in the traditional sense but because her rank in person–her medical expertise–puts her in the best position to make life-saving decisions. Her authority is recognized by the officers, who understand that in this situation, her expertise is more valuable than any title.

In real-world organizations, blending rank in position with rank in person can improve responsiveness and adaptability. A company may have a CEO and a strict hierarchy, but when a cybersecurity threat hits, the chief information security officer (CISO) often takes the lead, regardless of where they sit in the chain of command. In the same way, hospitals defer to senior surgeons in operating rooms, even though they may have less administrative authority outside of that setting. Organizations can prioritize expertise over formal structure when needed by allowing situational authority.

Ultimately, Kleck’s confusion highlights a real challenge in leadership: balancing the need for stable, clear-cut roles with the flexibility to let expertise take the reins. Organizations that recognize rank in person alongside rank in position can respond faster to complex, unexpected situations. For Dr. Chen, her authority isn’t about titles–it’s about having the right knowledge at the right time, and the confidence to step up when it matters.

Captain Kleck was just starting to understand human hierarchy, with its ranks, titles, and respect for position, when Dr. Chen completely upends his understanding. During a medical emergency, she overrides even the highest-ranking officer’s orders, and the general–a figure Kleck views as unquestionable–steps back. To Kleck, this is unthinkable; in Zexian culture, rank is absolute. Yet on the human base, Dr. Chen’s knowledge and quick judgment are what the moment demands, and even the general knows that her expertise supersedes his title in this crisis.

This concept, known as situational authority, allows the most qualified individual to lead, regardless of where they sit in the official chain of command. Situational authority is common in fields where rapid, high-stakes decisions are required. In emergency response teams, for instance, the incident commander takes control not based on rank but on having the most relevant expertise for the situation–whether it’s a medical emergency, a fire, or a hazardous materials spill. Similarly, in specialized projects, authority might shift to a technical expert or project lead when their skills are essential to the task at hand.

The benefit of situational authority is its responsiveness. The traditional hierarchy can become a bottleneck in complex, dynamic situations, slowing down decision-making as orders pass through multiple layers. By allowing authority to shift to the person with the right expertise, organizations can react quickly and effectively. Dr. Chen’s intervention in the story illustrates this perfectly. When time is of the essence, she takes charge, saving precious minutes that would be lost if she had to work through the formal chain of command. In this case, the general steps back because he understands that her medical expertise is more critical than his formal authority.

Situational authority isn’t just about expertise; it’s also about the trust and respect others place in the individual taking the lead. Dr. Chen’s authority is accepted not because she demands it but because the others recognize her knowledge and skill. This trust is essential for situational authority to work. Without it, individuals in crisis might hesitate or second-guess directives, undermining the swift action needed in high-stakes scenarios.

In dynamic organizations, situational authority provides a flexible framework for responding to fast-changing environments. Tech companies often embody this model in “scrum” or “agile” project teams, where leadership roles shift based on who has the relevant knowledge for each sprint. Similarly, hospitals and trauma units rely on situational authority, allowing senior medical staff to make calls that other healthcare workers follow immediately, regardless of their place in the hierarchy.

By adopting situational authority, organizations can cultivate adaptability–a key asset in today’s complex, unpredictable world. Leaders who recognize when to hand control to those with specialized knowledge empower their teams to make informed, effective decisions. Dr. Chen’s moment in the spotlight highlights this adaptive approach, where those best equipped to handle the situation are allowed to lead, ensuring the best possible outcome.

For Kleck, this kind of authority shift is profoundly alien, but it’s a way to increase human organizations’ resilience and responsiveness. By letting expertise guide action when stakes are high, dynamic organizations can respond quickly to evolving challenges, balancing the stability of formal structures with the adaptability of situational leadership.

For Captain Kleck and his Zexian crew, the concept of authority is wrapped up in visible ranks and formal orders. So, it’s no wonder they’re utterly bewildered by the human rituals that seem to carry invisible weight–like coffee breaks and casual interactions. To Kleck, the fact that humans take their coffee so seriously is bizarre. But what he misses is that these small rituals are part of a broader organizational culture that binds people together, fostering informal networks and reinforcing unspoken power dynamics.

Consider Dr. Chen’s “Doc Authority.” Beyond her formal medical expertise, there’s an unspoken respect for her role among the crew. This respect isn’t listed in any rulebook but is instead embedded in the station’s culture. Just as much as formal titles, these shared values influence who has authority in various situations. By respecting “Doc Authority,” the crew accepts that Dr. Chen’s guidance on health matters is paramount, even over traditional military rank. This shared understanding is part of the organization’s culture, making her influence felt even when her role isn’t spelled out in the chain of command.

Then there’s the coffee ritual, another source of mystery to Kleck. For the human crew, coffee breaks aren’t just a time to refuel–they’re also moments for informal bonding. Sharing a coffee is an opportunity to check in with colleagues, share ideas, and, perhaps most importantly, cultivate relationships that aren’t defined by rank. Over time, these small, repeated interactions build a foundation of trust and camaraderie that subtly shifts the organization’s power structure. Colleagues with strong informal connections often have more influence, as their ideas and opinions are shared and valued beyond official meetings or command structures.

In this way, organizational culture serves as the invisible scaffolding that supports formal authority. Culture-based rituals create shared understandings and unspoken norms that influence behavior, shape priorities, and determine who holds power in specific situations. The authority Dr. Chen commands, the camaraderie built over coffee, and even the deference shown to experience over rank–all of these are expressions of a deeper cultural fabric.

For Kleck, these rituals and informal hierarchies might seem irrational, but in many organizations, they’re the glue that holds everything together. They build a common ground that transcends titles, allowing a complex network of relationships, respect, and shared norms to thrive. In the end, organizational culture isn’t just a side effect of authority–it’s a powerful force that underpins it, guiding who holds influence in ways that no official structure can capture.

In many organizations, authority isn’t just about titles or rank–it’s also about relationships. Network theory explores how informal connections influence authority, allowing organizations to operate outside the limits of a formal hierarchy. In a networked structure, influence flows not just vertically (from higher rank to lower) but also laterally, based on knowledge, trust, and communication. Informal networks often enhance organizational flexibility, helping teams to adapt to changing circumstances with speed and precision.

Dr. Chen’s role in the story demonstrates a network-based approach to authority. Even without a formal military rank, her influence extends throughout the station because others recognize her expertise and trust her judgment. When a health crisis strikes, the crew doesn’t look up the chain of command; they look to Dr. Chen. Her authority flows through a web of informal relationships built on respect for her skills, experience, and clear-headed decision-making. Rather than being limited by her position, she wields influence that transcends official structures.

These networked relationships can be a game-changer in dynamic organizations, especially when quick decisions or specialized knowledge are required. Tech companies, for instance, often rely on cross-functional networks to tackle complex problems, with influence moving according to expertise rather than rank. In healthcare, crisis management often depends on tight-knit networks where doctors, nurses, and administrators can bypass traditional hierarchies to deliver the fastest and best care. These informal structures make organizations more agile, as decisions can be made based on real-time needs instead of waiting for approval through multiple layers of command.

The beauty of a networked approach is that it enhances decision-making agility, encourages collaboration, and fosters resilience in complex environments. By relying on networks of expertise and influence, organizations can respond more effectively to new challenges and avoid the bottlenecks that rigid hierarchies sometimes create. Dr. Chen’s authority, rooted in this network of respect and recognition, showcases how informal power operates as a crucial support structure, especially in critical moments.

In Captain Kleck’s rigidly hierarchical world, position dictates authority. But in the human station, influence flows through both formal and informal channels, weaving a dynamic web that helps the organization adapt, respond, and thrive. For Dr. Chen, this network-based authority isn’t an anomaly; it’s a key component of effective leadership in complex systems.

Captain Kleck’s experience on the human base may have been confusing, but it offers clear insights for leaders navigating complex organizations. As the story shows, effective power structures are more than titles and formal chains of command. They require an appreciation for expert power, situational authority, and the dynamic flow of influence that transcends traditional hierarchy.

First, organizations benefit when they acknowledge and support expert power and situational authority. Empowering those with the most relevant expertise, like Dr. Chen in a medical crisis, can make all the difference in critical situations. Leaders can foster this by actively recognizing and encouraging expertise-based authority within their teams, even when it operates outside the official structure.

Second, organizational culture should value flexibility. By encouraging situational decision-making, leaders allow team members to respond to challenges as they arise by fostering an environment where situational decision-making is encouraged. Whether through shared rituals, informal networks, or respect for specific roles like “Doc Authority,” creating a flexible culture strengthens an organization’s ability to adapt under pressure.

Balancing formal structures with network-based influence is another key lesson. Traditional hierarchy provides stability, but informal networks enhance adaptability. By weaving these together, leaders create a framework that can handle both routine operations and unexpected crises. For example, establishing cross-functional teams and supporting collaboration across roles encourages knowledge-sharing and increases organizational resilience.

Finally, organizations can establish protocols that recognize informal authority, especially for critical situations. Formal recognition of roles that operate outside typical hierarchies–for instance, assigning incident commanders in emergencies or designating technical leads on specialized projects–can help ensure that the right people are in charge when it matters most.

These lessons highlight the value of adaptable power structures in complex environments. For Captain Kleck, the blend of formal and informal authority on the human base is baffling, but for dynamic organizations, it’s a necessity. By designing power structures that respect both expertise and hierarchy, leaders can create a more responsive, resilient organization capable of meeting the demands of an unpredictable world.

Captain Kleck’s bewilderment at human authority dynamics may seem funny. Still, it highlights a severe truth: in complex organizations, adequate power often comes from a balance of formal rank and informal, expertise-driven authority. Titles and chains of command have their place, providing structure and stability. But as we see with Dr. Chen, real authority sometimes rests with those who have the knowledge and skill needed in the moment.

The story’s humor lies in Kleck’s struggle to understand this nuance, yet his confusion mirrors a common organizational challenge. Organizations can become more adaptable, responsive, and resilient by recognizing different bases of power–like expert power and situational authority. Understanding when to prioritize expertise over hierarchy doesn’t weaken an organization; it makes it stronger.

Reflecting on these dynamics, it’s worth asking how our organizations could benefit from informal authority and situational power. Are there ways to encourage expertise-based leadership or build networks of influence that operate beyond formal titles? By embracing rank and expertise, organizations can harness the best of both worlds, creating a power structure equipped to handle the complexities of today’s fast-paced environments.