Logarithms are one of the more remarkable transformations of mathematics. Remembering that for a given numerical base, , the value of and the special relationship of logarithms, . Using these forms, given one logarithm function, we can find the logarithm of any number in any numerical base.

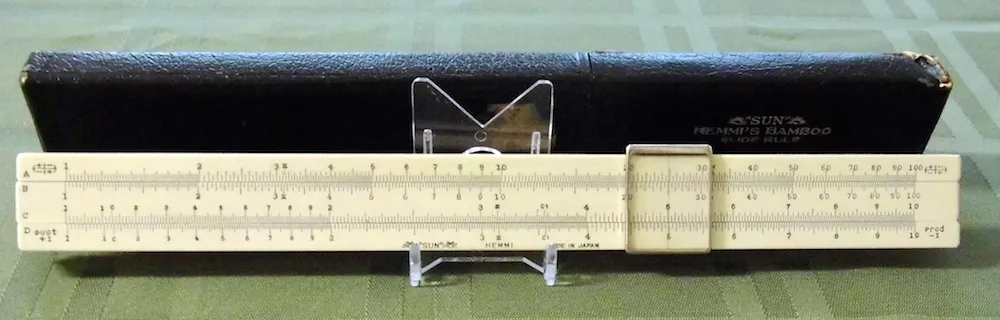

Generally, though, there are only three bases we would worry about. First is base 10, yielding the “common logarithm.” A logarithm in base ten essentially tells us how many digits there are in the number. This is useful for mental mathematics and is the basis for how slide rules work. Second, is base , normally called the “natural logarithm.” The natural logarithm’s base gives us a tool for analyzing growth rates and some statistical models. The final logarithm base 2, sometimes called the “binary logarithm.” The interest in binary logarithms stems from our modern data processing machines and tells us how many bits are necessary to store .

These different logarithm types are represented by various symbols. Different fields refer to the natural logarithm as , though some fields call it . For our purpose here, we will always specify the base when important and if the base is omitted, the statement is true regardless of base. Of course, some applications are base-independent. The base conversion formula, given above, works regardless of the underlying implementation base. Other applications, such as taking the logarithm of a data column before a regression analysis is also base-independent, provided you are aware of the implications of the logarithmic transformation.

Image by Joe Haupt / Flickr.