How Many Floating Point Numbers are There?

Wednesday September 09, 2015

The IEEE standard for floating point arithmetic provides for a noncontinuous space representing both very large and very small numbers. Under the standard, each floating point number are composed of three parts: the base, exponent, and mantissa. It functions just like scientific notation, but the base is not necessarily 10.

For traditional scientific notation, the base is 10, because humans are used to working with numbers in base 10. For double precision numbers, the base is not encoded in the storage. The base is 2 and is implicit. All IEEE data types use base 2. Accordingly, it would be redundant to store that information with each instance of a double precision number.

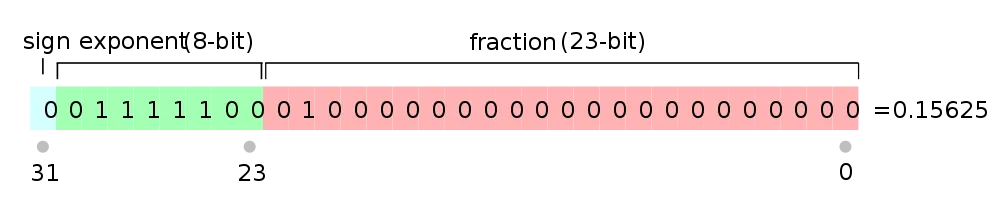

The primary part of the number is called the mantissa. This number encodes the significant digits of the number represented in the base. Since all double precision numbers are in base 2, this is binary. In this case of a single precision floating point number, 23 of the 32 bits are used to store the mantissa and a hidden implicit 24th bit available.

The final part of a floating point number is the exponent. The exponent, like the exponent on a number recorded in scientific notation, is the power the base is raised to, which is then multiplied by the mantissa for a final number. For a double precision data type, there are 8 bits available for storing the exponent, with one bit reserved for the sign of the exponent.

Finally, a single bit gives the sign of the number.

With these three components, a floating point number like 1000 is stored as,

where the 2 is never stored. Similarly, a negative exponent can represent fractional values.

Now let’s do some math. For any given value of the exponent, there are [latex] 2^{24} = 16777216[/latex] possible numbers that can be represented. However, the exponent decides how big that number will be. With a single bit reserved for sign of the exponent, 7 bits are available. This gives an exponent range of -126 to 127. For exponents from -126 to 0 (127 possible), there are [latex] 127 \times 16777216 = 2130706432 [/latex] possible bit combinations. And for exponents 1 to 127 (also 127 possible), there are 2130706432 possible bit combinations. But exponents from 0 down represent numbers less than [latex] 2^1 [/latex] and greater than 0. Exponents from 1 up represent numbers from 2 up.

As a result, allowing for some special carveouts to handle infinity, non a number, and other special floating point numbers, there are the same number of floating point numbers from 0 to 2 as there are from 2 to the maximum single precision number, around [latex] 3.402 \times 10^{38} [/latex]. The same logic also holds for double, quadruple, and other fixed-precision formats.

There’s a great single-precision floating point converter available on the web.

Image by Codekaizen / Wikimedia.